[Book Review] Ishmael

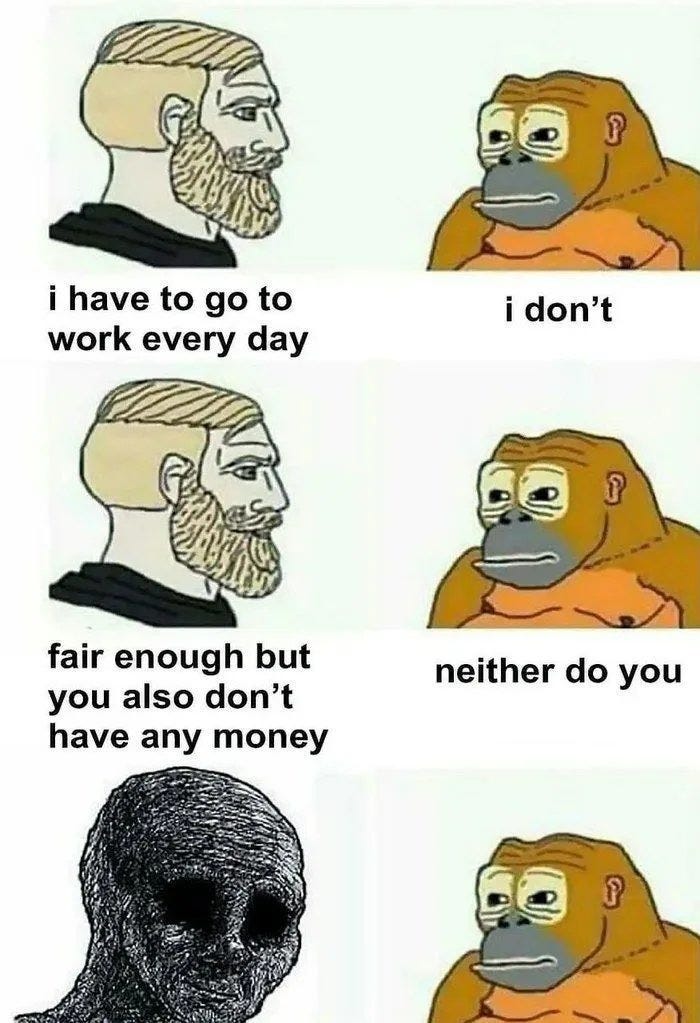

A discussion on the ecological and social nature of Man on earth. The original "Return to Monke."

Ishmael is a short-story by Daniel Quinn published in 1992. While it is decidedly a product of its time, it’s worth reading. It does include a number of classical and unquestioned anti-white tropes common in media of that time period. That said, the intellectual deconstruction of modernity is interesting, even if it contains facets of half-truths and radical over-simplifications.

Ishmael is a book that primarily exists as a dialogue between two characters. The first an classical liberal hoping to save the world, and the second, a magical talking gorilla named Ishmael who instructs the former on how to do so. While the framing of the resultant discussion is odd, it serves a purpose in the text.

The gorilla, Ishmael, acts as an external vehicle to analyze modern human culture. This permits one to examine human culture from an external perspective, key to understanding the valuable arguments made by the text. Before getting into that, however, we must consider the nature of the book based on the culture it emerged from.

When published, there was a sort of unfettered unity and the environmentalist movements were politically influential but tempered by economic interests. The era of the early 90s existed at “the end of history” in the opinions of many scholars, and so it was taken for granted that the future would politically resemble the present. Similarly, the book fails to account for the differences in western culture and distinctly non-western orthodox or far-eastern cultures. The failure is because, being at the “end of history” the book engages in the presumption that all future civilizations will acquiesce to a form of Americanized state-enforced liberalism.

Ishmael shirks the the spirit of the modern age by declaring all post-agricultural civilization to be complicit in planetary ecological destruction. It presents the culture of western civilization as a cage from which people cannot at this time escape. Most cannot even see the cage because they were taught to treat its boundaries as the boundaries of truth. Ishmael the gorilla and book creates a cognitive dissonance in the reader first by identifying that such a cage even exists.

“knowing that a trap exists is the first step in avoiding it.” ~Frank Herbert

Recognize first that there are ways of life that do not require subservience to managerial bureaucrats, submission to vast capital enterprises, or the observance of state law. Rather, those are convenient ways of life imposed upon humanity by collective cultural interests. Ishmael recognizes that fact and focuses heavily on the modernist and post-modernist cultural myths that drive acceptance of these identities.

The book, unfortunately, fails to distinguish between post-agricultural humanity and post-industrial humanity, lumping both together into a single identity. That identity is one that views the natural world as subject to the conquest of Man. The modernist myth that our place in the world is that of a king; bending ecology to our collective will.

The capacity to tame the elements, command the fire of gods and draw upon the very power of the sun allow us, as a species different from all others, to thumb our noses at the gods. To ignore the whimsy of fate and make for ourselves a paradise of this planet by consuming it. We deny the natural world its tendencies to alternate plenty and famine. Humanity have become kings contrary to the natural state of our ecology. Maintaining that crown requires slowly burning our kingdom to the ground.

Ishmael pairs well with many of the other books already reviewed on this substack:

Industrial Society and its future: A view of how industrial civilization is fundamentally breaking down human sociopsychology in the modern era.

The Ecotechnic Future: A view of how the future of human civilization might develop toward a post-industrial era as the critical resources for global industrialism grow scarce.

Breaking Together: A detailed analysis of the ecological damage done by human civilization and the way our top-heavy monetary system and elites will panic and flail rather than do anything useful to fix things.

Harassment Architecture: A psychotic break in literary form that delineates how the modern psyche is breaking down as micromanaged by the 21st century elites.

Starmaker: A long-term spiritual view of a civilizations quest for divinity. Tangential to the subject of Ishmael, but critical in developing ones understanding of the larger whole as viewed from beyond a single civilizations mode of being.

Ultimately, Ishmael posits that there are alternative ways of living life. That long ago in human history pastoral civilizations became the only mode of being driving out alternatives. Land must be tamed. Fields must be tended. Our development, while explosive, has occurred without wisdom. Ishmael suggest that the fundamental flaw of modernist civilization is the adoption of a cultural myth that places mankind at war with the natural ecology of the planet. The book suggests adopting an alternative cultural story; one where mankind was created to shepherd this world and its ecology rather than rule it as a king. A position of gently guiding the planet into a state of higher awareness and ecological complexity could act as the basis for a better way of life; solving many of the issues with industrial globalism by eradicating the contingent forces making it up.

When the book was written, the understanding of the public was primarily focused on how humanity damaged the natural ecosystem. The 90s were a period of incredible relative social stability to the point that “the end of history” didn’t sound as outlandish and narcissistic as it would today. In that way, Ishmael is prescient. The author well understood how temporary that era would be as resource scarcity and political instability broke down a seemingly stable Pax Americana.

The proposal that there exists alternative myths and modes of being other than industrial post-modernism is important. It is difficult for the modern man to properly imagine a world where he is not bound to the whim of midlevel managers or international global market forces.

The proposal of the book is simple: such a world exists, discovering and building it is something that can be done. And that doing so is a moral good.

30 years ago the text was somewhat ground-breaking work. It also tells the story with such literary flair that for such a short story it does get one to think. Which is probably the point. Despite a number of historical inaccuracies, or outright lies, it does provide a brief vision of what a better world and its ethos could look like.

Doubtless that current-year progressive revolutionaries, the type this book would have originally appealed to 30 years ago, despise the text. To them, there is nothing but the material, and any one who wants to create a better world is a right-wing extremist. Very strange how the times change. Stuck up old-guard bullies are the progressive left, while free thinkers of the right venture forth into a new spiritual ethos to build a better tomorrow for our children.

At the end of the day, Ishmael is the ultimate, and original, “Return to Monkey” meme.